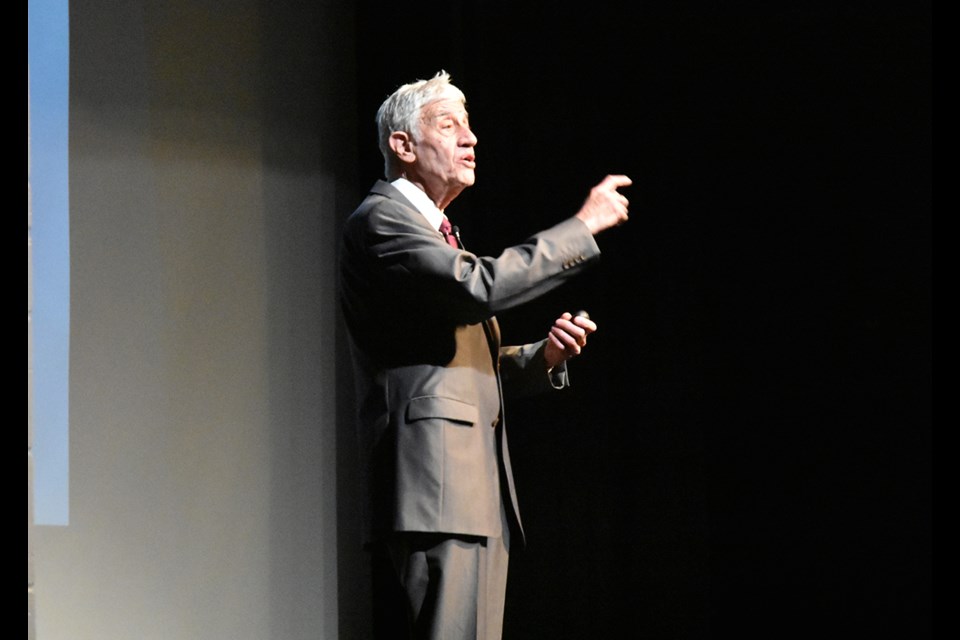

From a quiet life in Lithuania, to the Nazi-run Kovno ghetto and slave labour at the Dachau concentration camp, Holocaust survivor Elly Gotz recently spoke of his experiences to students at Bradford District High School.

He left them with a powerful message: “Hatred is a waste of time.”

Gotz, now 90 years old, was only 13 and dreaming of becoming an engineer, when his family was swept up in the Nazi horror of the Second World War. In 1941, they were among 28,000 people crammed into the Kovno ghetto without access to food or education.

In 1944, Gotz and his father were sent to Dachau and forced into slave labour. His mother was sent to another camp, and they did not know if she was dead or alive.

“Dachau was a terrible place,” Gotz said.

Labouring 12 hours a day, starving, he said the prisoners were set to work building a “bomb-proof” airplane hangar for the Nazis. The roof was constructed of five metres of metal reinforced with concrete.

To direct the flow of the cement, “our people had to stand on these narrow boards. The wind would push the boards sideways, and the prisoners would be blown off and drown in the concrete,” he said. “We were sick. We were dying every day. … All kinds of horrors took place in this camp.”

The hangar was never completed. On April 25, 1945, Gotz’s father, too ill to work, was on the brink of death.

With his father unable to stand in line for the watery soup and stale bread that was the only nourishment given to prisoners, he fetched the rations. As his father was eating, “people are screaming, ‘The Americans are here!’” The camp was being liberated.

All of Gotz's family survived the horror of the camps.

Gotz, weighing only 70 pounds when he was liberated, spent the next six months in hospital.

He said he came out a refugee who was full of hate.

“I hated Germans. I wanted to kill them. I wanted revenge. And then one day I said to myself, ‘What are you doing? That’s ridiculous.’”

He said he realized it was ridiculous to blame 40 million Germans for the actions of a few. It was the Nazis who believed “all Jews are terrible people, and now you are saying the same about them.”

That was a turning point. “I gave up my hate, and that’s when I started to live,” said Gotz.

He went to Norway, one of the few countries that accepted Jews liberated from the camps, and he taught himself Norwegian in three months by reading newspapers, using a dictionary, and stopping strangers in the street to converse.

He got a job in a radio repair shop, and then moved to Africa, ending up in the former British colony of Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe.

Gotz learned English, pored over books, and finally achieved his childhood dream — a university degree in electronic engineering.

There were no jobs for electronic engineers in agricultural Rhodesia, so he started his own businesses: a sound recording studio, an advertising agency, and a film company.

He learned to fish, shot crocodiles, rode horses, and climbed mountains.

“I was living. I wanted to experience life,” Gotz said.

In 1958, he met and married his wife of 60 years, Esme. The couple moved to Canada in the 1960s, where he launched new businesses and fulfilled another dream by learning to fly a plane.

Last year, to mark Canada’s sesquicentennial, he went skydiving for the first time at the age of 89.

“We live a wonderful, happy life,” he told the Bradford students.

So why relive the experience by speaking to students and other groups?

“I come to tell you how it is possible that genocide can occur,” Gotz said, adding it starts with personal hatred. “We are not comfortable as human beings when we meet someone different than ourselves. It’s ridiculous.”

He urged the students to be curious about people who are different, noting, “you will discover our common humanity.”

To go from personal hatred and prejudice, to genocide, two other elements are needed, Gotz said: “You need a country that says it’s OK to kill. You need a politician who says it’s OK to kill.” He urged young people to pay attention to politics and what is said by politicians, and to reject attempts to blame one group or another in tough times.

Gotz said he has rejected hatred but not necessarily forgiven those who engineered the Holocaust.

“You don’t have to forgive unless they ask for forgiveness, but hatred is a waste of time.”

The visit was arranged by Bradford District High School history teacher Brent Dyck, as part of the Grade 10 curriculum, which looks at the events of the 20th century.

“He’s amazing. He’s such an inspiration,” Dyck said.

About 300 Grade 10 and 11 students attended the local presentation May 2.

Grade 10 student Danveen Randthawa presented Gotz with a gift bag from the school and was immediately encouraged to go into engineering by Gotz, who told her, “we need more women in engineering!”

“It was amazing,” Randthawa said. “It was an honour to listen to that story. We learn about history, but this was the experience of history.”